Bryan Cyril Thurston in his studio: the ambivalent depiction of the artist by his son also points to the potentially anachronistic nature of 1970s activist Romanticism.

Xenix Filmdistribution GmbH

A new documentary about British-Swiss artist Bryan Cyril Thurston makes a nuanced case for the power of art as a form of environmentalist activism.

“The private is always political, and the political is always private,” an old truism declares. “All art is political,” notes another.

Greina, the new documentary by Swiss architect and filmmaker Patrick Thurston, charts both the utopian potential and the at times sobering repercussions of these principles.

The film takes its name from the Greina mountain pass in the Lepontine Alps, which straddles the border of the Swiss cantons of Graubünden and Ticino. It reflects Thurston’s attempt at grappling with the artistic and personal legacy of his 91-year-old father, English-born painter, engraver, and architect Bryan Cyril Thurston.

A prolific visual artist who has lived in Switzerland since 1955 – and whose oeuvre, containing some 5,000 pieces, is archived in the Swiss National Library – Bryan Cyril Thurston is today perhaps best remembered for his art-inflected environmentalist activism that brought him certain national prominence in the 1970s and 1980s.

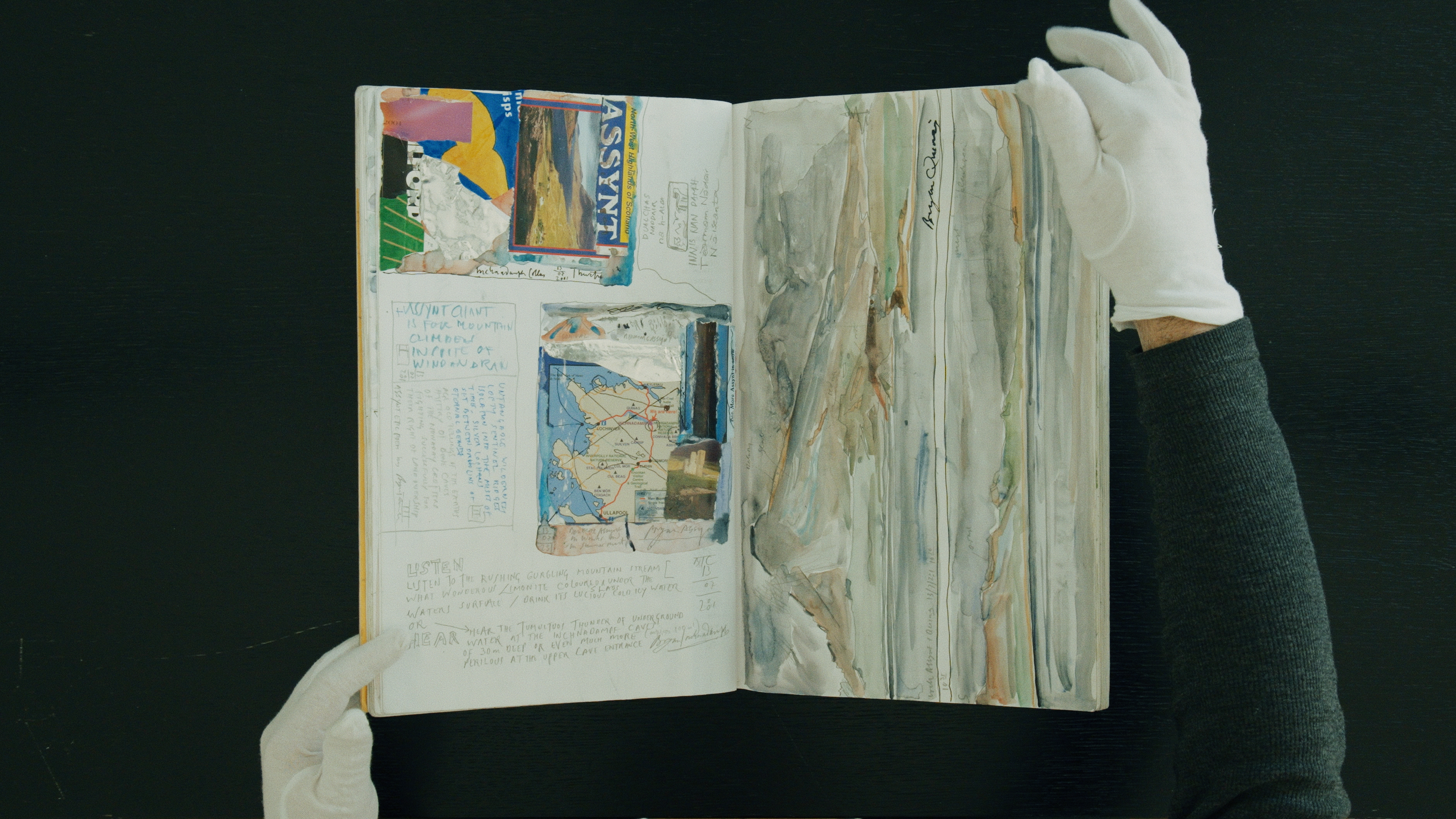

Travelling sketchbook of Torridon, Scotland by Bryan Cyril Thurston (2001).

Xenix Filmdistribution GmbH

The early days of eco-artivism

In those years, plans were underway to build a hydroelectric dam on the Greina plateau, in an effort to economically revitalise the nearby villages of Vrin and Sumvitg. If it had gone ahead, the project would have flooded the Greina and turned the pristine Alpine landscape into an artificial lake.

Bryan Cyril Thurston, an avid hiker who had fallen in love with the plateau and its mountain vistas (which reminded him of the Scottish Highlands), could not bear this idea.

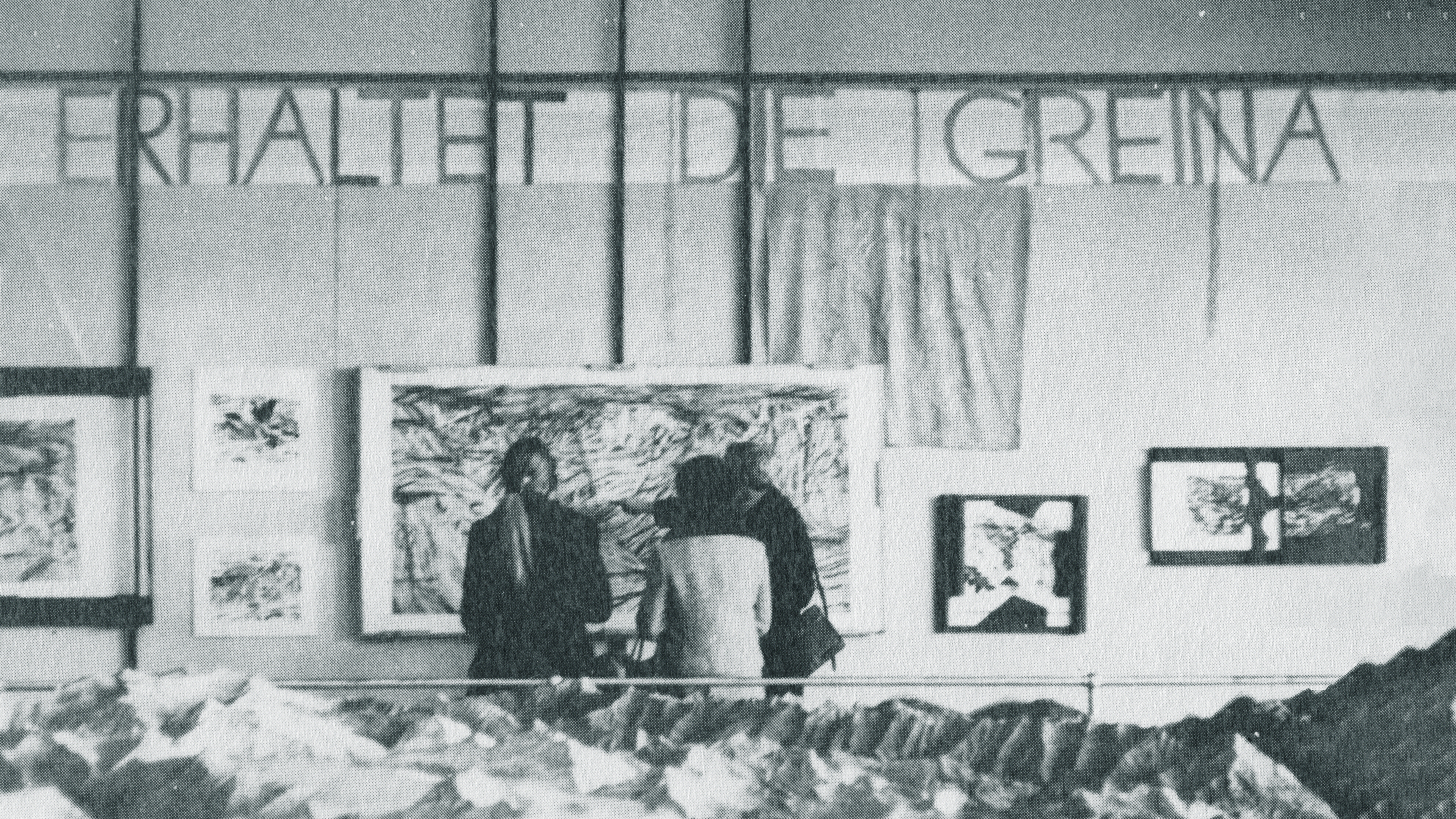

He took a stand and helped galvanise a movement of artists, who organised numerous exhibitions dedicated to protesting the dam project. “Kunst als aktiver Landschaftsschutz” (“Art as an active form of environmental protection”) and “Nur die Poesie kann die Greina retten” (“Only poetry can save the Greina”) were Thurston’s idealistic rallying cries.

“Greina” exhibition at the Geological Institute of the federal technology institute ETH Zurich, 1975.

Xenix Filmdistribution GmbH

Improbably, this decades-long campaigning effort was ultimately successful. The dam was never built. Vrin and Sumvitg received compensation for the financial losses incurred, paid for by the Landschaftsrappen fund, which rewards communities for opting out of building over natural heritage sites in favour of environmental protection.

An old battle anew

The preservation of the Greina was very much in keeping with the zeitgeist of the mid-1980s, coinciding with the nascent environmental movement and societal fears about forest dieback. In his artist’s statement on the film, Patrick Thurston also links the success of his father’s campaign to the 1989 decision to scrap the planned nuclear power plant in Kaiseraugst, near Basel.

It’s a provocative memory to revel in at this historical and cultural moment, as Switzerland has been engaged in a heated political debate over its energy supply in recent years. Faced with fears over potential shortfalls, exacerbated by Europe’s uncertain geopolitical situation, such discussions have become a familiar election-season refrain.

Patrick Thurston in front of his father’s three-part Greina triptych in Olivone, canton Ticino.

Xenix Filmdistribution GmbH

While left-leaning parties tend to advocate for an easing of regulations regarding the building of wind turbines and photovoltaic panels, the right’s preferred solutions include the expansion of the country’s hydroelectric capabilities. Most recently, and much to the chagrin of the left, the Swiss government issued a recommendation to lift the existing ban on the construction of new nuclear power plants – a ban that the Swiss voters had only approved in 2017.

In other words, Greina is being released into a political and social climate that is maybe as roundly unsympathetic to the notion that poetry and the sublimity of the natural world take precedence over Switzerland’s economy and energy independence as it has ever been.

Family issues

Not only does this lend the otherwise rather conventionally realised film a potent political undercurrent; it also adds an intriguing layer of meaning to the 65-year-old Patrick Thurston’s on-screen attempts to (re-)connect with his father.

The pair’s interactions – part interview, part studio inventory, part family history lesson, part talking therapy – suggest a son eager to find closure on a fraught relationship and a father being reluctant to concede that there is anything to talk about. And this apparent mismatch is expressly bound up with the elder Thurston’s artistic-political engagements.

A passion for drawing unites father and son.

Xenix Filmdistribution GmbH

According to Patrick, “there was a deep chasm between myself and my father. As a child, his efforts to preserve the Greina seemed like a hopeless and absurd battle between David and Goliath, a battle that kept my father from being there for me.” As inspiring as the Greina campaign might have been politically, in private, “those were bitter years, dry spells that finally needed resolving.”

Greina – and, by extension, Patrick Thurston – thus finds itself caught in two minds. Although it unambiguously celebrates the triumph of environmental activism and artistic creation over economic rationales, as symbolised by Bryan Cyril Thurston, it also wrestles with the considerable personal cost of this triumph.

Lessons from Utopia

Far from a weakness, however, this internal conflict underscores both the thorniness of the topic at hand and the dangers of seeing the story of how the Greina was saved from being “put to economic use” only in nostalgic terms.

Yes, the documentary is emphatic in its conviction that the present – and the environmentalist movement in particular – can and should learn from the utopian dreams of half a century ago, that there is something to be said for making the environmentalist case on philosophical and aesthetic rather than on purely pragmatic grounds.

Yet Patrick Thurston’s ambivalent depiction of his father also points to the potentially anachronistic nature of such activist Romanticism. Bryan Cyril Thurston, an almost stereotypically English type of affable curmudgeon with an affinity for the late Prince Philip, is, in a sense, the very model of a self-styled white male saviour inserting himself into a social issue and claiming authority of interpretation.

The Plaun la Greina plateau (2,200 metres above sea level) between Surselva (canton Graubünden) and Blenio Valley (canton Ticino).

Xenix Filmdistribution GmbH

It’s hard to imagine such an approach resonating with today’s more collectivist and praxis-oriented environmentalist movements such as Fridays for Future or Extinction Rebellion – let alone a Swiss Green Party eager to prevent environmental destruction through traditional broad-based policymaking that considers voters’ anxieties over energy security.

Still, as a piece of politically conscious art, Greina does ask a range of pertinent questions, including where initiatives like Thurston’s Greina campaign have gone. Nature, both Thurstons seem to agree, is too important to leave its fate up to the politicians.

Edited by Virginie Mangin/ds

More